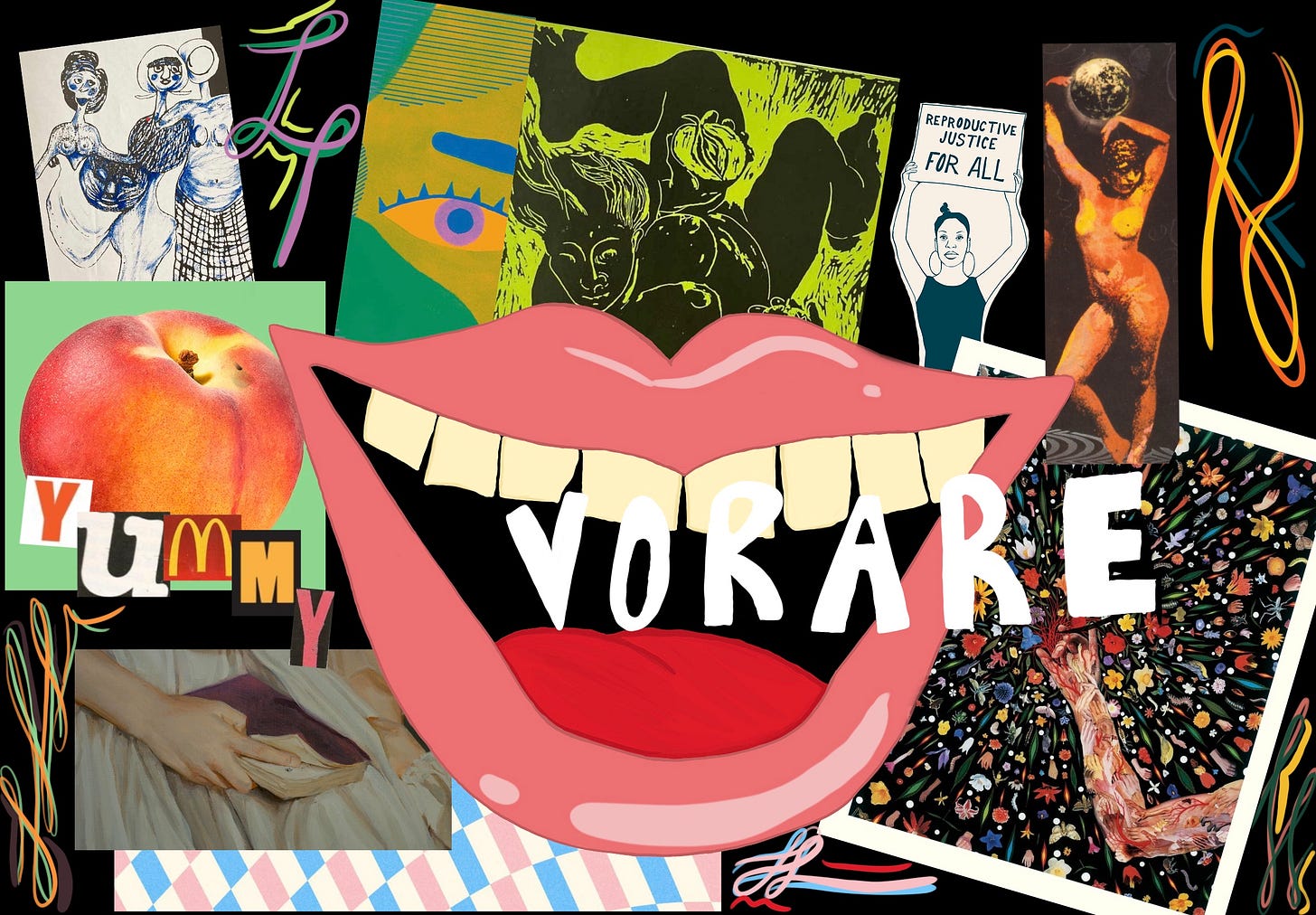

Bienvenue et bon appétit!

/voˈra.re/: to devour, swallow up

As a feminist writer and researcher, there seems always to be immense pressure to produce: to churn out essays, and articles, and reviews, and publications. It is, after all, insufficient to align myself with feminisms and feminists but not to carry out feminist acts with feminist results; feminism is an enactment, something I must do. It is intensely rewarding to create things that touch and move and connect me to people, devoting myself to big ideas and to their expression. That’s why I stick with it—to grow into myself and toward other persons (and hopefully magnetize them my way). This fulls me up. It is also, for me, at times debilitating, stomachaching. An anxious person, constantly dancing and seemingly teetering on misstep, I’m fearful of creating unintelligent or—worse—uninformed and unimportant texts. What if I never reach the people with whom I’m desperate to commune, or—heaven forbid—I deter and repulse them? Self-conscious ruminations.

What never ceases to please me, sate me, and what does not feel painful or tenuous, is my engagement with the works, thoughts, and art of others. Of course, these others are executing the very above mentioned labour that I find at times draining and I’m effectively leeching, preying, on that—but hopefully not unreciprocatedly. I will, I intend, eventually return to the world some of that which it has given me—create a corpus into which people may sink their teeth. But until then, I receive satisfaction from consuming, devouring, gorging myself on the platters of others. I am voracious, insatiable, at times bloated from and retentive of the dishes on offer. One day, I’ll generate a tasty recipe from the buffet of pages and frames and brush strokes and music notes and movement on which I’ve indulged. Until then, the least i can do is anthologize, what Ahmed has called, my “feminist toolkit” or, what I might (to keep the figuration unbroken) consider as, my icebox. In the end, how can I prepare a feast without proper comprehensive inventory of what I have in the fridge and what I still need from the shops? Without a clear notion of what flavours pair well and which conflict? I must learn the necessary internal temperatures of meats to prevent food-poisoning. I must simmer, savour, digest, improve (if never to perfect), and then share my meal. This newsletter is dedicated to my gluttony—to my porcine proclivities and to a gentle, tentative, affectionate report of the thoughts that arise from rapid overconsumption of all things delicious and stimulating. This is the itemized stocking of my pantry. Or, this is an appetizer to, a tasting menu for, some eventual grand dinner party. This is a living-room in which I’m glad for you to join me as we drink wine and eat hastily-prepared hors d’oeuvres. And since we’re amongst friends, there can be no pressure placed on me to write dense and beautiful prose in abundance and I shall not be held fast to what I have written. I am still, as yet, only ever masticating (granted, with my mouth open).

Without further adieu, let’s get in to our first ever family dinner (my belaboured and imperfect metaphor signifying regular reviews and explorations of texts that’ve kept me company the previous week).

MATRIX, Lauren Groff

“Perhaps the song of a bird in a chamber is more precious than the wild bird’s because the chamber makes it so” (45)

“Everything possible with everything given has been done” (248)

A more careful and loving review to follow for my first “chef’s special” (see my about page). But, for now, let me say that this story encapsulates an attentiveness to pleasure and care without being saccharine or performing femininity as something fragile or soft and it makes me feel loved and calls on me to be loving. Much of the book is bound to the minutiae (as is seen by the repetitive invocation of prayers and chores) and small complications of surviving with and for others. Some have described it as a dream of female Utopia, but that feels reductive somehow; I don’t think “perfection” is at any point the goal. While there are grand projects and visions being realized over the course of several decades to ensure the nuns’ safety, wellbeing, and flourishing, there are incessant conflicts arising from which Marie and her cloister continue to learn and grow, evincing and bolstering their mettle. The book can read almost as a series of vignettes in which each ambition or dilemma is assessed, discussed, and then resolved and, like life, regardless of the outcome of particular incidents, everyone and everything just keeps plugging along doing their level best. Each character is individual, charming, and flawed. The story is all the more beautiful because love and care and joy occur both because and in spite of all that stands against them (which, I think is nicely enveloped by the two above quotations that bookend the narrative); the strife that hinders joy also varnishes it.

LOLITA, Vladimir Nabokov

“please, reader: no matter your exasperation with the tenderhearted, morbidly sensitive, infinitely circumspect hero of my book, do not skip these essential pages! Imagine me; I shall not exist if you do not imagine me; try to discern the doe in me, trembling in the forest of my own iniquity; let’s even smile a little. After all, there is no harm in smiling. For instance (I almost wrote ‘frinstance’), I had no place to rest my head, and a fit of heartburn (they call those fries ‘French,’ grand Dieu!) was added to my discomfort” (120)

No one feels good after reading Lolita, surely. No one reads it and thinks “this is such a good story for me to bring to my friends and summarize for them the plot.” And that’s good that people feel icky about its narrative events. Not everything is bound or meant to make us feel good. It might in fact be beneficial to read and then discuss the book to pinpoint exactly what it is that is so bad about it—evidently, the strategies and justifications that adult men might use to exploit and abuse children. But despite yourself, you might indeed smile in moments like the above when you face the fully-realized and absolutely neurotic Humbert Humbert’s raving and ranting. What a nervous mess. What a worm. Humbert is an anxious, despicable, pretentious dork that Nabokov writes wonderfully. I laugh out loud at the above quotation where he is bumblingly desperate to conjure something like sympathy by attempting to control the narrative and, by extension, the reader. But I also see Nabokov coming out here—in Humbert’s plea, he confesses that we readers have the power, that Humbert does not exist if we do not imagine him. It is important that we approach with critical minds his tale and thereby we do not allow the version of him he would have us believe to materialize. He needs us to believe him, and we must not be dupped. Dolores is similarly lifelike, both flawed and loveable, and has resonated with me for days now adding to the sympathy I feel for her. Despite it all, she is a willful and generous person, she is terribly aware, cunning, and funny. I’d written on Goodreads how I find it troubling and fascinating that Humbert is meant to be the author who has represented this Dolores to us in such careful detail. How does that change how we think of her (if it does) and how does it change what we think of him and his relationship to her (if it does)? Was she really such a vibrant and vivacious girl with a rich emotional intelligence? Or does he benefit in manipulating her into one for his account of events?

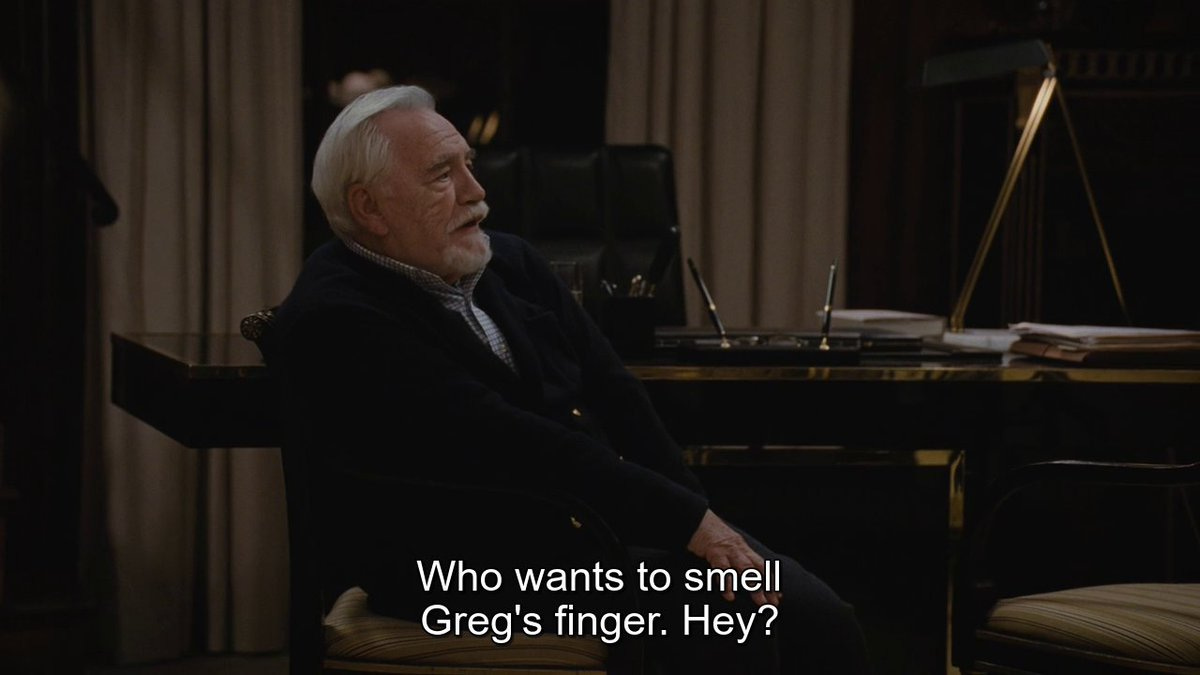

SUCCESSION, HBO

Like the rest of the world, lately I’ve been captivated by Succession. The first season, I must confess, did not much move me. But, in anticipation of this fourth and final season and encouraged by accolades from friends, I persevered and my efforts were not in vain. I learnt to deal with the camera operators’ incessant heavy-handed zooming. Mr. Darcy eventually was allowed to become Tom, in my mind (though I’m still hoping for some Siobhan-related hand flex action). The final episode of the first season hooked me with what felt like a shift in not only the tone but the genre of the show—suddenly there was a crystallization of certain crime-tv motifs as well as the evident family and corporate dramas which appeals to me. I probably couldn’t really care less about the future of a megalomaniacal media conglomerate. But the sequence of Kendall trying to reassimilate into his sister’s wedding after letting a boy die and Logan subsequently exploiting his son’s vulnerability displayed exactly the kind of batshit pathological psychology I like to observe and unpack. While the dialogue can be zippy and fun (though at times pandering to the zoomer crowd), the overarching writing, the plotting, leaves something to be desired. That is, I’ve noticed that several characters and threads get introduced but are left to drop or hastily resolved. Is no one else interested in what happened to Roman’s girlfriend, Tabitha? What’s up with Logan’s sister Rose? Why was Rhea even a character? Sometimes it seems the characters and the narrative events are haphazardly assembled in service of pithy one-liners rather than the dialogue beefing up the story. I’m confident I’ll have more to say as the season progresses, but for now, I’ll leave it there.

Are you still with me? If so, (thank you and) you might as well come back next Sunday! This has been a longwinded welcome to Vorare!