I’ve long been interested in the cultivation of non-romantic and extra-familial relationships——specifically, in connections formed and sustained by a shared passion. If you don’t have any skin in the game, carnally or biologically, what drives you to play on someone’s team? What reasons do people find to stay near one another, to build intimacies when unburdened by filial or sexual motivations? While it seems evident that, for it to work, camaraderie, like inherited and monogamous relationships, requires commitment and loyalty and effort, there appears to be less creative energy paid to the demands and rewards of devoting oneself to ardent friendships and to the trickiness of that type of closeness——to the laborious ways that people nurture amity even when it grows tedious whether because of physical or emotional distance. We might justify why someone sticks with their spouse through thick and thin or why they remain dutiful to their difficult parents and siblings, but we might not be so understanding when someone continues with an onerous friendship. Why is it that friendships can be made redundant with greater ease than other bonds? What’s more, too often passionate and powerful attachments are assumed to be sexual and romantic or to have the potential to mutate from the a-romantic into something sensual as though the true source of any heartfelt association is latent romantic energy. Some of the tenderest and most dynamic connections are platonic, though as readers and viewers we sometimes interpret them as romantic. Perhaps this phenomenon occurs as a way to more easily make sense of a meaningful attachment since eros is the normative and privileged mode. We “ship” characters, pairing them off as a couple, or read for the pornographic in ways that undercut the vastness of the erotic. This practice cheapens things for me. Can we talk about the erotics of non-sexual relationships? Can we talk about unwavering devotion in friendships? Should we consider fostering connections even when they do not always make us feel “good” or “positive,” but instead bring out the worst in us? This week’s offering of books and TV has made this line of enquiry resurface for me.

THE BEAR

The critically-acclaimed TV show The Bear follows a chef, Carmen “Carmy/Bear” Berzatto, as he returns home to take over the family restaurant, The Original Beef of Chicagoland (great name), after the passing of his older brother. I appreciate this show for effectively triggering anyone who’s worked hospitality. I only briefly worked under-the-table alongside a bunch of nonnas as a server in an Italian club, yet still I can testify that the pressure, intensity, and gruffness of The Beef kitchen is accurate to a T. As someone who becomes overstimulated cooking with the extractor fan on, I was beside myself during the second to last episode and very impressed with its organized-chaos choreography which my partner, Aidan, rightly described as “in the style of Noah Baumbach.” This is one of those shows that can be a little corny, but on the whole I think is enjoyable and relatable and nicely directed. It is true that some of the arcs are shallow and it does not track to me that the employees of a neighbourhood greasy spoon would adopt high culinary behaviours if just given the slightest crumb of approval or out of fealty to the late owner and his little brother. Even if this is meant to be a narrative about the hard-working working-man who finds pride in his work and in feeding other hard-working working-men, the move to elevate the worker by enforcing kitchen standards beyond basic health, safety, and hygiene expectations seems classist——let dives be dives and let working-class food be delicious without complicating it by making it aspirational of something more. Why does it take two young educated and worldly chefs coming in to impart their wisdom before this middle-aged kitchen staff feels like their work is purposeful? Screw a ribbon of brine, give me a grilled cheese. What I would like to see (and what probably would be more accurate) is back-of-house employees who work hard and fast and also do not give a shit about their verbally abusive boss, the restaurant and its prestige, or even their job, at the end of the day. Sydney walking out of that shit-show made total sense to me, and I’m surprised no one got stabbed earlier. Still, for each moment when I cannot suspend disbelief, there will be some heartening and hilariously faultless counterpoint. Certain characters, for example, are very well-constructed, like Richie, aka Ebon Moss-Bachrach, aka Desi from Girls. While everyone must confront the fact that Carmen “Carmy/Bear/chef/Jeff/too-many-nicknames” Berzatto, and for that matter Jeremy Allen White, is not a dirtbag (and so the internet must quit it with these so-called greaseball thirst traps of him), Richie most definitely is a scumbag. In this episode of I Saw What you Did, Millie and Danielle brilliantly and helpfully breakdown the distinction between the two.

To bind this series with my theme of friendship and foes, we have the dynamics between Richie and Carmy, and Carmy and Sydney which are none of them entirely amical nor familial, and certainly not sexual. Instead, Richie and Carmy are tethered by their love for and mourning of Carmen’s brother, Mikey. Sometimes, to love someone who loved someone that you loved is the best way to go on loving someone, even if——especially if——they’re difficult to love. On the other hand, Carmy and Sydney’s bond is more complex to me. They are tethered by a passion for food and excellence in their craft. Sydney supports Carmy, despite his melodrama, because of admiration for him. To be in awe of someone is a cogent reason to stand by them. Conversely, though Carmen recognizes in Sydney some greatness, he momentarily resents Sydney her culinary gifts as though there can only be one talented cook in the kitchen, as if there is finite genius to go around. I wouldn’t call this relationship a friendship per se, but it’s also not strictly professional nor antagonistic. These are two individuals whose passions incline them to one another, and this gravitation can be potentially generative or volatile as is explored at various points in the first season. Having a comparable drive to someone is like walking the razor’s edge: you either adore them infinitely for all the ways they are akin to you and better you, or begrudge them for the ways they differ and (appear to) surpass you. Either way, however, you are attracted to them for the ways they inspire extreme emotion, love and hate. I can see future seasons of this show playing on this difficult balance as the characters continue their collaboration.

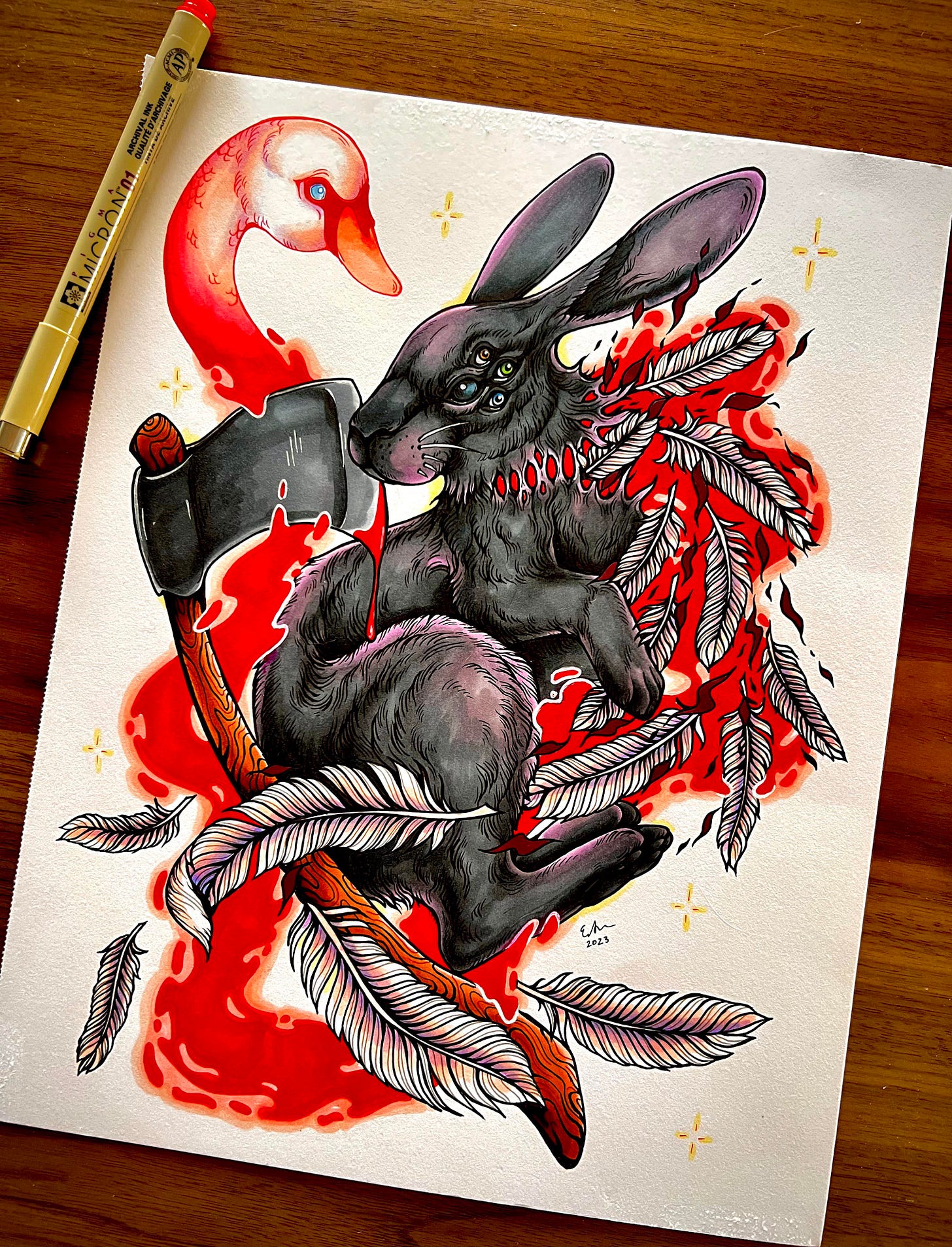

BUNNY

Perhaps in preparation for my triumphant return to academe, I’ve stocked my TBR with novels about (unhinged) grad students (stay tuned for some Donna Tartt). First on my list was Mona Awad’s Bunny. Goodreads and Bookstagram queued me for a deranged and morbid tale, but what awaited me was something a little too Y/A witchy fantasy for my taste and also slightly grating. Many have likened the novel to Heathers and The Craft and I agree with the comparisons. The book pokes fun at the cultishness of higher education, the variety of people you find in the University (or lack thereof), and the ways that a group of literature students might interact with one another in collegiality and adversity. It takes class privilege as a central concern and critiques how some students must earn their education with creativity and “hard work,” while others can simply extort and buy it. The novel draws motifs from a wide number of classic texts like Alice in Wonderland and Frankenstein and references several modern and contemporary works which will leave the literary reader feeling well-read and snobbish.

At it’s center, we have Samantha Heather Mackey who is excluded from her insular cohort of four other women who all refer to one another as “Bunny” and take drugs that sate them so they can continue ritualistically exploding bunnies that, once sacrificed, are converted into these ideal romantic heroes of the young women’s imaginations. The Bunnies’ friendship rallies around the fabrication of perfect sexual partners which they unfortunately can’t seem to get right——we see the privileging of eros even from within a group of close friends (and Alison Bechdel is away somewhere weeping). When the girls invite her in, Samantha goes along with this for some time because she longs for companionship. We know early on that she’s a loner who only has one friend that is, as we discover by the end of the book, only a figment of her imagination conjured up from a swan and that the same terrific creative powers that allow her to transmute a fowl into a friend would surely benefit the Bunnies build-a-boy business. It’s a little convoluted. But a lot of the story is propelled by a desire to commiserate with others and to feel a sense of belonging. So much so that you would kill and die for it. Curious to me is the affection between Samantha and her swan friend, Ava, who she declares at some points to be her soulmate and with whom there are definite homoerotic overtones. While an argument could be (and definitely has been) made about the queer elements of the text, I’m interested instead in reading it as an allegory against romantic love and the pursuit of a (singular) perfect match. Bunny concludes that you can’t force, fashion, or forge your true love, and you can’t fake your way through a friendship, but you can open yourself to the world, make yourself vulnerable to harm, and only then you might find someone (like Jonah) with whom to pass the time.

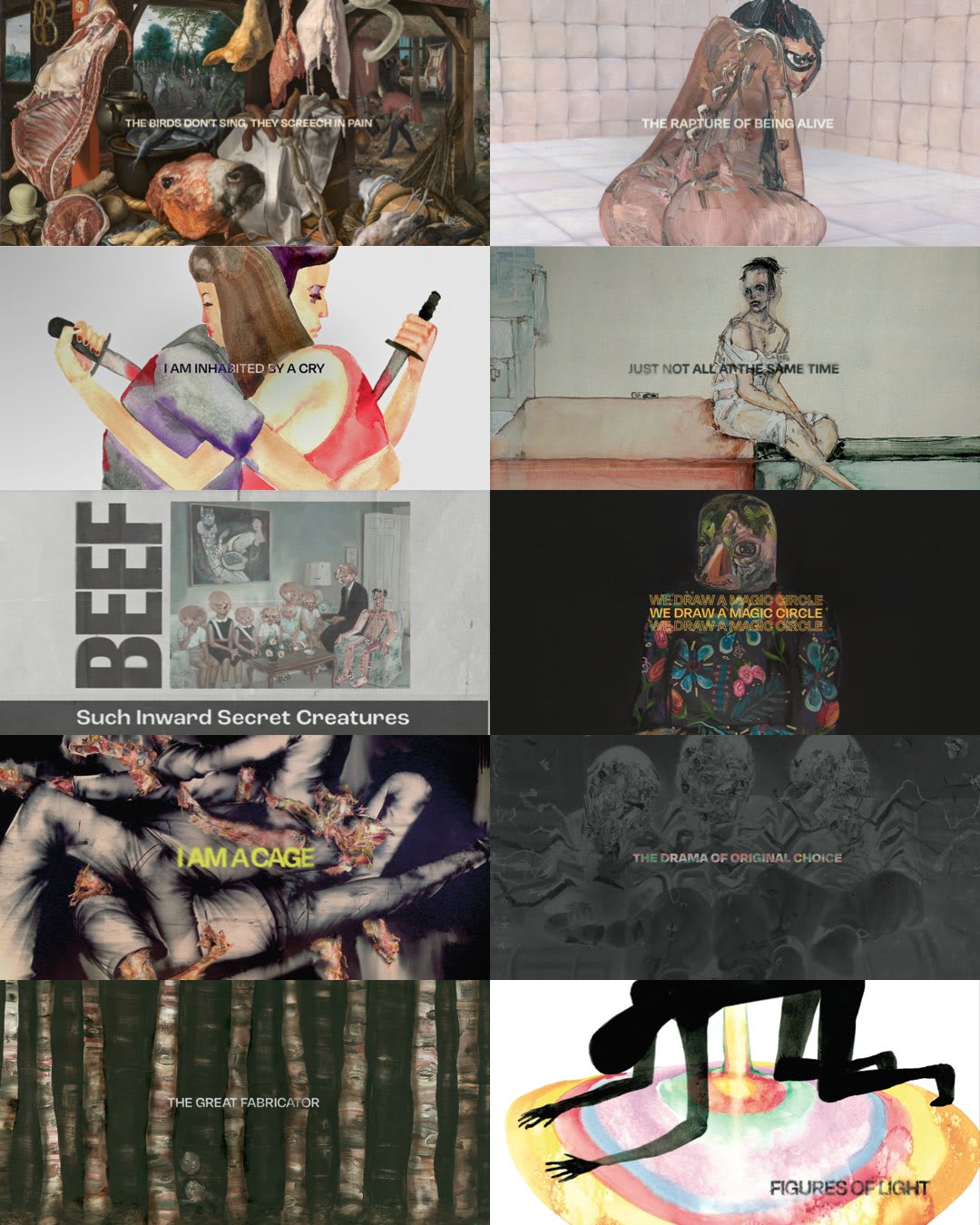

BEEF

I contend with people who think that A24 are the absolute arbiters of contemporary movies. I was therefore apprehensive of Beef. I was like “here we go, another move in their monopoly.” And while I didn’t think that the series was world-changing and earth-shaking, I thought it was fun and lovely, aesthetically beautiful, sad, and thoughtful. Steven Yeun can do no wrong and to watch him weep in church was truly spiritual. Ali Wong has been a comedian whose stand-up I’ve followed for some time, and to see her perform a straight and at-times quite emotionally intelligent if not manipulative character made a wonderful change that spoke to her wide range. The casting was as spectacular as the title-sequence art.

As you no doubt have guessed, what compels me in this series is the non-romantic connection between Amy and Danny. Have I ever seen anything else quite like it? It begins with a textbook road rage incident and continues to compound as these characters try to get back at one another and in doing so become entangled in the trajectories of each other’s lives. Finally, they both implode their own relations along with the other’s and end up in the wilderness, alone together, where they can find common ground, empathy, catharsis. It is so important to me that Amy can then confess to Danny that her nuclear family does not make her feel any less alone——that she does not know if they feel to her like home. We see a crack in the privileging of heteronormative ideals. She sees through the illusion of unconditional love and this both wounds her and opens the door to more and deeper points of connection. As with most limited series that gain traction, there is push to extend the story for another season——I think this would be disastrous. I anticipate netizens will advocate for the closeness between the leads to escalate into something other than what it is and that the final scene of physical proximity will be misread as bodily attraction. But it isn’t and can’t be about that. No. Lee Sung Jin is showing is how careful and practical a nemesis might be. Amy and Danny demonstrate the extremes of that before-mentioned razor’s edge of deep intimacy——the tricky predicament where being so alike another, so passionately connected to them, entangled also with their relationships and families, even momentarily going so far as to inhabit them, drives us to obsession and abhorrence. For these two, the negative affects they feel seem also to help them be less alone——at least they feel something for someone, which is real and tethers them to the world. Yet these negative drives are no less powerful and, even though negative, they are magnetic rather than repellent. Keeping your enemies close might not necessarily be strategy for war; it might be a tactic for wellbeing.

Anyways… Remember to tell your friends you love them and to reassess your nemeses!

I am also writing something about our conversation about writing hehe <3 very lucky to have thoughtful friends with whom I can have endless conversation!!